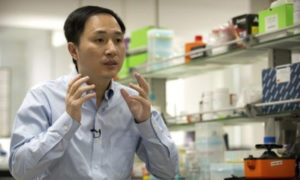

Chinese researcher He Jiankui has claimed that he used CRISPR to produce the world’s first “designer babies”. On Wednesday, he said a second pregnancy was underway. A look at the genetic editing tool that may change our relationship with genetics for better, worse or both.

Why is CRISPR in the news?

He Jiankui has claimed that he produced the world’s first genetically-edited babies. Jiankui said he used CRISPR—Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats—to alter the genes of a pair of twins while they were embryos to make the babies resistant to HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. He said a possible second pregnancy had resulted from his project. The announcements prompted mostly criticism from other experts in the field. Using CRISPR to make changes to embryos and germline cells—sperm, eggs and zygotes—is contentious as the modifications are passed to progeny.

Can genetic editing prevent serious diseases?

In 2017, a US science and medicine advisory group decided to support research using technologies such as CRISPR to modify human embryos for prevention of serious diseases and disabilities. In experiments with human cells, CRISPR has been used to repair a mutation that causes blindness and correct the defect responsible for cystic fibrosis. The first human trial began in China in 2016 using CRISPR-modified T-cells to treat lung cancer patients. Two studies published in mid-2018 found that cells edited by CRISPR have the potential to seed tumours, raising the risk they would trigger cancer, but the link is still under investigation.

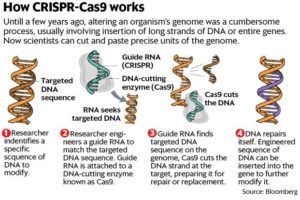

What is CRISPR-Cas9?

CRISPR-Cas9 is a rudimentary immune system first noticed in bacteria nearly 30 years ago. They are sequences of genetic code broken up by remnants of genes from past invaders.

How is CRISPR used?

In 2012, researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, published a paper on making molecular “guides” that allow CRISPR to skim along DNA, targeting exactly the right spot to make a slice. Then, scientists at Broad Institute said they’d adapted it for use in human cells. A researcher with basic skills and equipment worth a few thousand dollars can employ CRISPR. The gene-editing system isn’t perfect yet: it makes unintended cuts in DNA as often as 60% of the time in some applications, with effects unknown.

What’s the argument against using it?

Decisions about whether to use CRISPR to treat people who are already sick could be made through traditional consideration of risks and benefits, once they are better understood. The potential to do good is enormous: eliminating a genetic disease from a family forever. But if something goes wrong, the consequences are potentially eternal, too, affecting future generations who could not give prior consent. Some scientists worry that germline editing would invite enhancements of babies for non-medical reasons.

The development was reported by livemint.com