New Delhi: On a balmy evening last week, Sandeep Singhroha, a farmer from Haryana’s Karnal district, set fire to a pile of paddy stubble with a matchstick and then dragged the pile across his field with a garden fork. Soon, the two-acre plot was up in flames, making a steady crackling sound interspersed with guitar-like notes as parts of the dried straw burst open in the searing heat. As the fire settled, a thick blanket of smoke covered the field. The impact was immediate: eyes started burning and breathing became difficult.

New Delhi: On a balmy evening last week, Sandeep Singhroha, a farmer from Haryana’s Karnal district, set fire to a pile of paddy stubble with a matchstick and then dragged the pile across his field with a garden fork. Soon, the two-acre plot was up in flames, making a steady crackling sound interspersed with guitar-like notes as parts of the dried straw burst open in the searing heat. As the fire settled, a thick blanket of smoke covered the field. The impact was immediate: eyes started burning and breathing became difficult.

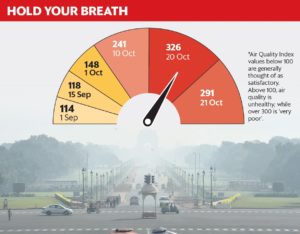

Every year, through October, thousands of farmers across Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh set fire to an estimated 23 million tonnes of paddy straw. The crop is harvested with combine harvesters, which leaves behind a foot long stubble on the field. Since the straw cannot be used as animal feed, farmers set fire to it to get the field ready for the next crop of wheat. The short window of about three weeks between the harvesting of paddy and sowing of wheat—since a delay in the planting of wheat beyond the first week of November leads to lower yields—means that thousands of hectares of land go up in flames simultaneously. Over the weekend, an estimated 2100 fields were on fire (according to satellite data), which along with the burning of countless Dusshera effigies, plunged air quality across much of northern India to ‘very poor’ levels.

The centre and state governments have proposed machine-driven solutions and incentivized farmers with subsidized machinery to end the practice of stubble burning. But Singhroha will have none of it.

With a part of his paddy crop lost to untimely rains last month and a loan of Rs.25 lakh which he owes to local moneylenders, he doesn’t want to take any chances, or add to his costs by hiring human hands or machines to clear the field. Why bother when a matchstick is so cheap.

The blame game

There is no precise estimate on how much stubble burning by farmers contributes to Delhi’s recurrent tryst with unbreathable air. However, a recent study by the Harvard University pegged that “post-monsoon fires” pump about 150 micrograms per cubic metre of fine particulate matter (PM) into Delhi each day. For comparison, the World Health Organization (WHO) safe air standard over a 24-hour period is 30 micrograms of PM. The fires, the study found, double the already high pollution load, taking PM levels to roughly 12 times over WHO recommendations.

But the smoke drifting in from outside is only part of the problem, because source apportionment studies which try to ascertain the origin of the pollutants have repeatedly indicted the vehicular emissions in Delhi for the problem. The capital not only has the highest number of cars in the country, but also the total number of vehicles on the road doubled twice in the last 8 years.

“The share of transport emissions has increased by 40% since 2010, more within the city than in the neighbouring areas, while that of the industrial sector (within Delhi) has increased by 48%,” said Gufran Beig, project director, System of Air Quality and Weather Forecasting and Research (SAFAR).

Thus, while stubble burning has emerged as an intractable, unsolvable annual puzzle, things have dramatically worsened even within the geographic confines of the national capital region. “What we are doing to mitigate air pollution is not enough, or we would have seen results,” said Chandra Bhushan, deputy director general, Centre for Science and Environment.

Unhappy seeder

Palvinder Singh, 43, bursts out laughing when told that the Punjab government has announced a global innovation award of $1 million to find a solution to the annual stubble burning ritual by farmers. “No machine or technology is cheaper for the farmer than matchsticks which cost 25 paisa,” he said. “Every year, you keep adding cars to your cities and people in Delhi take the easy way out by blaming us,” Singh, who farms on 40 acres of land in Haryana’s Kaithal district, added.

In March, the centre approved a Rs.1,152 crore package that focused on mechanized solutions. Under the scheme, individual farmers will be eligible for a 50% subsidy, while a group of eight can get the necessary machines at 80% subsidy. Despite this, farmers have shunned the technological fix, which uses a combination of machines, such as straw management system (SMS) and happy seeder.

“The number of machines currently available to farmers, either owned or on rent, is good for straw management in one-tenth of the land farmed in Punjab,” said Jagmohan Singh, a farmer leader from Patiala in Punjab. Further, he complains that after the government subsidies were announced, manufacturers quickly raised the prices substantially. An SMS priced at Rs.65,000 last year costs more than double the amount this year, several farmers from Haryana told Mint.

Farmers also say that using these machines for straw management cost upward of Rs.5,000 per acre, and more importantly, they fear a 10-15% loss in yield if the happy seeders are used for planting wheat.

“Happy seeders can lead to a lot of unhappiness,” said Palvinder. Happy seeders plant wheat seeds into the soil and cover it up with the chopped straw. The process saves on ploughing costs, but farmers fear a loss in the wheat yield, besides the added concern that the wheat crop may be prone to fungal infection due to the decomposing straw. Singh also says farmers will need to use heavier and more powerful tractors to pull the happy seeder, spending more on diesel and rent.

“I cannot understand why the government is pushing the zero-till (no ploughing) happy seeder technology down the farmer’s throat,” said Devinder Sharma, a Punjab-based agriculture policy expert. “We are forcing farmers to use newer machines which are of use for only a month in a year while making machines that they already own redundant. In the end, it is the manufacturers who stand to benefit,” he added.

The way forward

Instead, Sharma suggests direct financial payouts to farmers, about Rs.5,000 per acre, and then leave it to their choice to use either labour or machines to clear the straw. There are long-term fixes too. Palvinder, for instance, supplies his entire stock of paddy straw to a paper mill. However, the entire district has only one paper mill.

At least some farmers who defy the ban on stubble burning end up getting fined. But while the fine amount is Rs.2,500 per acre, proper straw management costs Rs.5,000.

“So tell me what I should do?” asks Sandeep Singhroha, smiling.

The development was reported by livemint.com