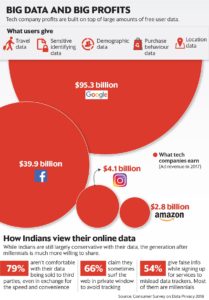

Alphabet Inc.’s Google, Facebook Inc., and other tech giants offer us free internet services. And every time we use these services (in fact, Google tracks us even when we are not consciously using it), they collect data about us. From basic demographics to our secret desires, from our movements to our objects of hatred. It’s a boundless ocean of data about us that is fed to the artificial intelligence (AI) programs lurking behind these services. These are the most powerful surveillance machines the world has ever seen, which know a lot about what we are doing at any moment as long as we are carrying a smartphone.

Alphabet Inc.’s Google, Facebook Inc., and other tech giants offer us free internet services. And every time we use these services (in fact, Google tracks us even when we are not consciously using it), they collect data about us. From basic demographics to our secret desires, from our movements to our objects of hatred. It’s a boundless ocean of data about us that is fed to the artificial intelligence (AI) programs lurking behind these services. These are the most powerful surveillance machines the world has ever seen, which know a lot about what we are doing at any moment as long as we are carrying a smartphone.

Your data is crunched along with data from millions of other users so that the algorithms can learn and generate enormous profits for the companies. These are earned through what is still called “advertising”, but should possibly be called “behaviour manipulation”. Because Facebook not only knows to a great degree of precision whether you are the right person to be served a particular advertisement, but can also judge with some accuracy when should the ad appear on your wall, based on your past behaviour—maybe four seconds after you have “liked” a cat video, or violently disagreed with someone on the Sabarimala issue.

Now, consider the AI revolution that is supposed to engulf our lives in the near future. Many professions are already facing extinction. But more than “artificial intelligence”, AI is “collective intelligence”.

AI algorithms are not created in a flash of inspiration by genius programmers. The process works thus: enormous amounts of human data is collected (Big Data), and through machine learning, algorithms are created to fit the data. As more and more data comes in, through adaptive feedback, the algorithms become more and more accurate.

Data creates profits

It is the data—which we give away for free—that is the core of the vast profits of the world’s most valuable companies. Facebook, for example, pays only 1% of its value to its workers (programmers), because the rest of its work it gets free from us (Walmart pays 40% of its value in wages).

So, a small number of smart people become extraordinarily wealthy and the rest don’t get anywhere.

However, a few visionaries have been trying to introduce a radical new concept—“Data as Labour (DaL)”—that will make for a far more economically fair society in the digital age. The idea was first mooted by virtual reality pioneer Jaron Lanier in his 2013 book Who Owns The Future?

In other words, we should get paid for the data that we provide these companies because that is the real source of their profits. Hence, our online interactions are “work”. For instance, how would Google ever be able to direct us to our destinations without collecting data from the smartphones of millions of car drivers and passengers?

The tech companies today treat data as capital, which comes to them at no cost. Think of a company that is building nursing robots, which could become a reality sooner than we think. To create these robots, the company will collect huge amounts of data on how efficiently human nurses go about their work. The irony is that these robots will ultimately replace these nurses and take away their livelihoods because now they have ingested and been programmed with all the data these humans have generated—for free.

Or consider the Google translation software. It constantly searches the internet for translation work being carried out in the public sphere; captures that data; and the algorithms use that data to produce more accurate results.

Languages are living entities, changing over time, with new words, expressions, idioms and slangs being added ever so often. Google is constantly monitoring all this activity and making its translation function more and more precise. There may come a day when professional translators will be put out of business by Google, which has developed its expertise by gorging—without any cost—on all the data that these people have been generating. Should not the translators have been paid?

Throughout human history, profession after profession has become obsolete due to technological progress. But usually, this has meant people upgrading their skills and getting better-paying jobs. When horse carriages were replaced by automobiles, carriage drivers became car drivers. In the print media, when the job of the cut-paste artist became defunct, he quickly learnt page-making software. But in the coming revolution, all of us can hardly become AI programmers. There will be massive job losses and possibly social unrest.

Users are generally unaware of the riches that they are creating for the tech titans through their online interactions. But there is a massive transfer of wealth taking place in our economies that may lead to a disturbingly inegalitarian future.

Siren servers

In the early days of the growth of the internet, when the idealists were in charge, there came to be some sort of a consensus that the internet would be a medium for free exchange of information and ideas. So how would the firms make money?

Entrepreneurs turned to the advertising model. And advertising needed targeting of consumers. The result was that a few clever people built what Lanier calls “siren servers”, gigantic computational facilities that could out-compute anything else on earth. This led to enormous user bases which used the services for free in exchange for their data. These firms became monopsonies (a market situation in which buyers are few and sellers are many) whose interests, by definitions, lie in keeping prices low—in this case, the price of data, on which they could build their empires.

In the last few years, there has been growing awareness of the user’s rights to his data, though principally through the data privacy route. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulations, which came into effect in May this year, give people extensive rights to check, download, and even delete personal data held by companies. That is a beginning.

Competition could be another way forward. If other tech giants like Microsoft Corp., Apple Inc., and Amazon.com Inc., which use some free data but are far behind Google and Facebook on this, and also on the AI front, start paying, it could force the Big Two to follow. Google already outsources work like testing the efficacy of its searches to more than 10,000 human beings (and pays them), but had been trying to keep it a secret.

A third way could be if data labourers unionised and could collectively bargain with these companies. No individual has any bargaining power, but a union that can filter access to user data could possibly call a powerful strike.

As Lanier et al write: “Such a union could be an access gateway, making a strike easy to enforce. On a social network, where users would be pressured by friends not to break a strike, this might be particularly effective. A union could also be useful in certifying data quality and guiding users to develop their earning potential.”

The first such union was launched in the Netherlands in May this year—Datavakbon or Data Labour Union. It hopes to elect leaders to directly negotiate with Google and Facebook over what they do with users’ data.

According to Reuters, “volunteers are working on tools to make it possible for the union to organize a ‘strike’, which would involve temporarily depriving the companies of some of the most valuable information they sell to advertisers, such as location data. Possible demands could include payment for the data that users supply to the companies; more information about how the data is used; and a direct channel for communicating grievances.” Membership is free.

But how do you price data as labour? The first hurdle is that the concept blurs the boundaries between work and leisure. After all, much of the data the monopsonies are glutting on is produced during consumption rather than any dedicated activity. This will require a great amount of economic and technical sophistication.

However, the production function for AI may not be too difficult to measure because the relevant machine learning algorithms and their performance at different times and with different data sets are usually well-documented, at least within the companies. Research is already on to determine the marginal effect of new data on predictions, though there are several conceptual and technical questions that still need to be worked out. This could be very useful for valuing data.

Win-Win for all

The funny thing is that Data as Labour could even help the tech titans in the long term, though in the short run, their profits will be squeezed. As AI grows more advanced, it will require more and better data.

Right now, through their surveillance, companies get mostly random data. As AI services get more sophisticated, algorithms will need to be fed a higher-quality diet of digital information, which people may only provide if they get paid.

In a recent book, Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy For A Just Society, Glen Weyl, an economist at Yale University, and Eric Posner of the University of Chicago, write: “Appropriate technological systems have to be developed for tracing and tracking the value created by individual users. These systems would have to balance a number of competing concerns.

On the one hand, they should try to measure which individual user is responsible for what data contributions, especially when these contributions are disproportionately large, and/or these individuals would be unlikely to supply or invest in this unique data that make these exceptional contributions unless they are monetarily incentivized. Creators of valuable entertainments, experts in obscure languages who can aid computer translators, specialized masters of video games who can help teach computers to play them expertly in multiplayer settings, these are unique skills worthy of exceptional rewards. On the other hand, tracking every detail of the ordinary use of a Facebook post would be overkill, and certain classes of data should be ‘commoditized’ and paid an ‘average price’ based on meeting basic quality standards.”

Maybe all this seems somewhat far-fetched. But the times we live in today, the things we do, what we see around us, would have seemed utterly incredible even 30 years ago. Google is only 20 years old and it’s already possibly the most powerful company on earth. Facebook was set up in 2004. Things can change very fast.

The development was reported by livemint.com